After all that talk last time about how I’m not gonna read textbooks anymore, here I am with another reading project. This book just happened to catch me when I was low on both ideas and time, so reading just made the most sense.

If Microservices in .NET was a little below my level, then this book was definitely a much better fit. I found it particularly relevant in my new job, especially since many of the patterns and practices discussed were present in the codebases I’m trying to learn. If you’re already familiar with the topics discussed here, then you already understand like 70% of the book. The last 30% is just code examples using the different libraries and technologies discussed in the book.

Below is an assortment of facts and information I found most useful from the book. Great pains were taken to keep this post at a reasonable length because the book covers a lot of material.

Properties of Microservices

Containers are more or less analogous to a single running process, but it is possible to run several processes inside a container.

Microservices allow you to scale out individual parts of your application, as opposed to containerizing and replicating a monolith. This makes deployments more efficient.

If you know how to build a microservice-based application, you also know how to build a simpler service-oriented application.

Each microservice:

-

Encapsulates a specific domain or business capability within a “context boundary”.

-

Must be developed, versioned, deployed, and scaled autonomously/independently.

-

Should “own” its own data model/database and domain logic.

Try to keep your microservices small, but don’t make this a priority. Focus on keeping your services independent and loosely coupled.

Microservices should maintain their own domain data and domain logic. Ideally, each service reads and writes to its own database.

Microservices are The concept of microservice derives from the Bounded Context (BC) pattern in domain-driven design (DDD). DDD deals with large models by dividing them into multiple BCs and being explicit about their boundaries. Each BC must have its own model and database; likewise, each microservice owns its related data. to the Bounded Context (BC) pattern of Domain-Driven Design (DDD). Read up on this on your own.

Each Bounded Context may be comprised of multiple services, and each service may be comprised of multiple sub-services sharing the same data.

Benefits of a microservice-based solution

Downsides of a microservice-based solution

The new world: multiple architectural patterns and polyglot microservices

The API Gateway Pattern

Your client applications can communicate with your backend in one of two ways:

-

Direct client-to-microservice

-

API Gateway

A direct client-to-microservice communication architecture could be good enough for a small microservice-based application, especially if the client app is a server-side web application like an ASP.NET MVC app.

When using direct communication, be cognizant about how many requests are hitting your backend, and see if you can try to reduce them (eg. aggregate requests or use a load balancer). It can also be difficult to manage cross-cutting concerns like logging and authorization using a direct communication scheme.

API Gateways act like a Facade or reverse proxy into your services. They are a great way to decouple your clients from your microservices. They provide several benefits.

Clients only need to know the address of one service (the API Gateway) as opposed to keeping track of several microservices whose address may change.

API Gateways are located much closer to your microservices than the client, and also have the option of aggregating requests for the backend, making communication much faster.

Routing requests through an API Gateway reduces the attack surface of your application.

Since all requests go through the API Gateway, this is a perfect spot to handle cross-cutting concerns like authorization and SSL.

Despite this, there are still a couple of pitfalls when using the gateway pattern.

It is easy for a gateway to become bloated with features, especially if it is serving multiple clients. Consider using multiple gateways to serve different parts of the application (around your business boundaries), or using multiple gateways for serving different types of clients (backend for frontend).

Usually it isn’t a good idea to have a single API Gateway aggregating all the internal microservices of your application. If it does, it acts as a monolithic aggregator or orchestrator and violates microservice autonomy by coupling all the microservices.

Your API Gateways are naturally coupled to your services, and may inadvertently tightly couple some services together.

API Gateways are a single point of failure, and may become a bottleneck if not scaled properly.

Microservice Communication

An eventual consistency strategy should be used to propagate updates in your application state. Eventual consistency is normally implemented using event-driven communication and a publish-subscribe system.

You may run into the CAP theorem when designing your applications.

Opt for asynchronous communication strategies like message- or event-based communication or polling. Avoid communication using HTTP call chains as much as possible. HTTP requests made between microservices introduces coupling, increases response latency, and makes your system more fragile against failures.

Asynchronous communication helps to further decouple your microservices from each other.

While you should prefer asynchronous communication most of the time, there may be situations where synchronous requests may be valid.

-

Any request that can be performed in less than a second.

-

Services that use RESTful endpoints.

Asynchronous communication is typically implemented by making use of and event bus/message queues to store your messages/events, which other services can then read from and handle appropriately. Some solutions include RabbitMQ, Azure Service Bus, NServiceBus, MassTransit, and Brighter.

Developing Microservices

You may use technologies like Swagger, Swashbuckle, and NSwag to automatically generate documentation about your API endpoints.

When using an event bus to implement asynchronous communication, you will typically be sending “integration events” through it, which are used to propagate changes across multiple microservices or external systems.

Your integration events are typically just data-holding classes:

public class ProductPriceChangedIntegrationEvent : IntegrationEvent

{

public int ProductId { get; private set; }

public decimal NewPrice { get; private set; }

public decimal OldPrice { get; private set; }

public ProductPriceChangedIntegrationEvent(int productId, decimal newPrice,

decimal oldPrice)

{

ProductId = productId;

NewPrice = newPrice;

OldPrice = oldPrice;

}

}

Using an event bus is pretty straightforward:

public interface IEventBus

{

void Publish(IntegrationEvent @event); // `event` happens to be a keyword in C#, so we use @ to escape it.

void Subscribe<T, TH>()

where T : IntegrationEvent

where TH : IIntegrationEventHandler<T>;

void SubscribeDynamic<TH>(string eventName)

where TH : IDynamicIntegrationEventHandler;

void UnsubscribeDynamic<TH>(string eventName)

where TH : IDynamicIntegrationEventHandler;

void Unsubscribe<T, TH>()

where TH : IIntegrationEventHandler<T>

where T : IntegrationEvent;

}

You still have to write a client that talks to the underlying event bus technology though.

Remember that your events are transmitted using a network call, and all the inconsistencies and errors that come along with that. There are several strategies to handle the case where an event may fail to publish.

Ideally, your events should be idempotent so that any events that may have been accidentally sent multiple times won’t corrupt the application state.

CQRS

Command Query Separation (CQS) states that you can divide a system’s operations into 2 types:

Queries - these return a result and do not change the state of a system (no side effects).

Commands - these do change the state of a system.

CQS can be applied at the function, object, and system levels. Operations should either return state or mutate state, but not both.

CQRS is an extension of CQS covering more advanced scenarios.

Your UI elements are often heavy senders of queries.

Implementing CQRS helps when following DDD since certain constraints are placed on transactions and updates.

Queries should be idempotent no matter how many times they run.

Commands are meant to make changes, and have business logic to do so. Make sure that you apply your logic correctly if using DDD.

DDD (Architecture)

These are not hard guidelines nor is this a real introduction to DDD. This section just goes over some design patterns that might be worth using.

DDD advocates modeling based on the reality of your business. When building applications, DDD talks about problems as domains. Independent problem areas are called “Bounded Contexts” (where each BC correlates to a microservice). It also emphasizes a common language to talk about these problems. It prescribes various concepts and patterns to support the implementation of your services.

Note: not all DDD vocab was explained in the book.

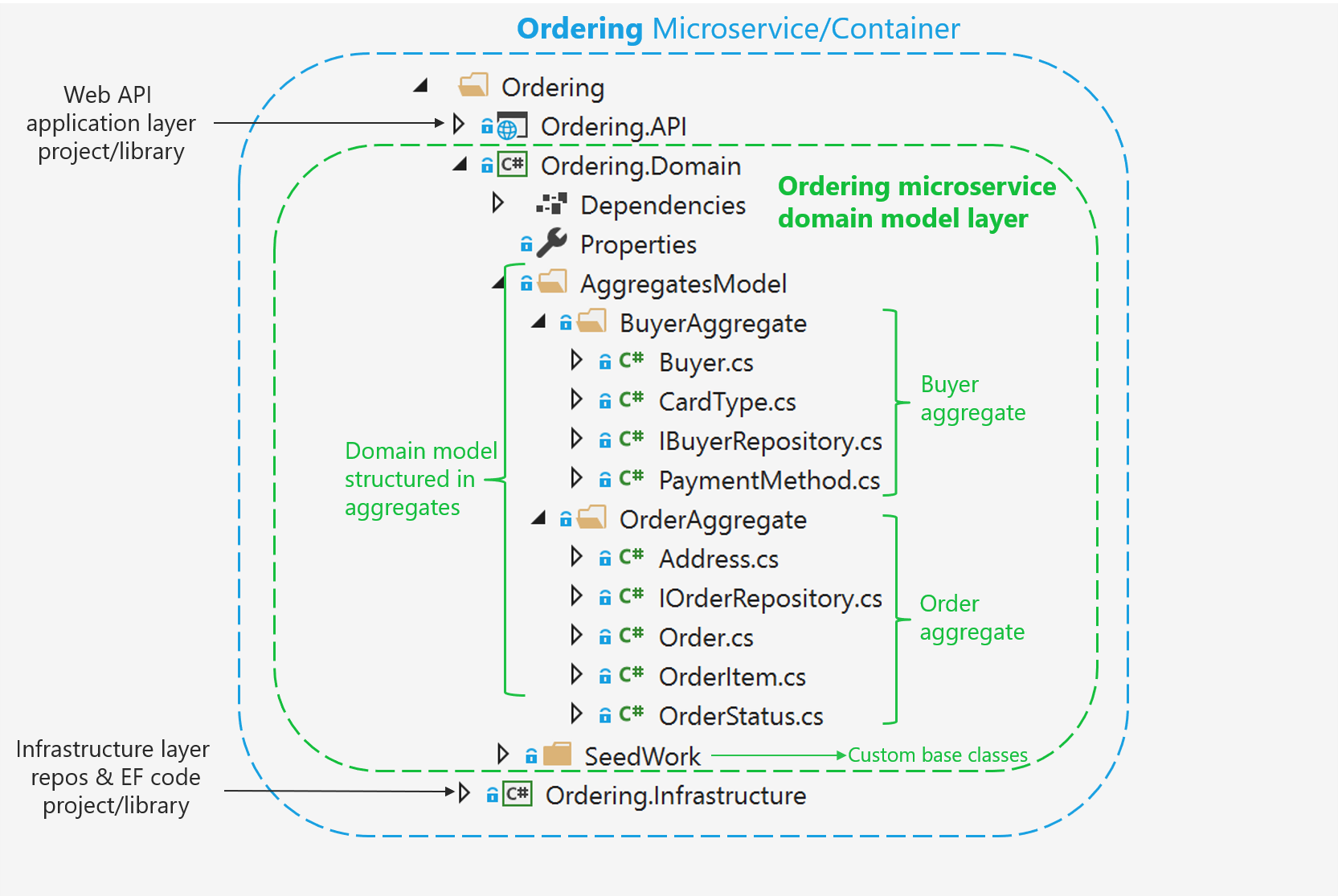

It may be useful to structure each individual microservice as a set of layers. The book uses a 3-layer approach. Each layer may be implemented as its own project (eg. a Web API or just a class library).

The Domain Model Layer contains and represents business concepts, information, and rules. All your domain state and domain logic should be implemented here.

Your domain model is typically implemented as a class library in your microservices. This library contains domain entities that capture data and any associated behavior/logic.

This layer should have little to no dependencies, and should be agnostic to any particular persistence infrastructure or other services you may be using. It typically does this by defining the interfaces that your infrastructure layer will later implement.

This is analogous to the root package of the Go Standard Package Layout.

The Application Layer allows your service to interact and be interacted with other services. Here you might define the structure of your (web) API and wire up your dependencies and connections to other services.

The application layer must not contain business rules or domain knowledge. It simply services to coordinate tasks. This is like your main package in your Go projects. The application layer processes requests by handing them off to the proper domain model that should perform any queries/updates.

The Infrastructure Layer manages the implementation of any database/persistent storage for your application. This includes the database itself, as well as any code that accesses it, like EF Core.

DDD (Domain Modeling)

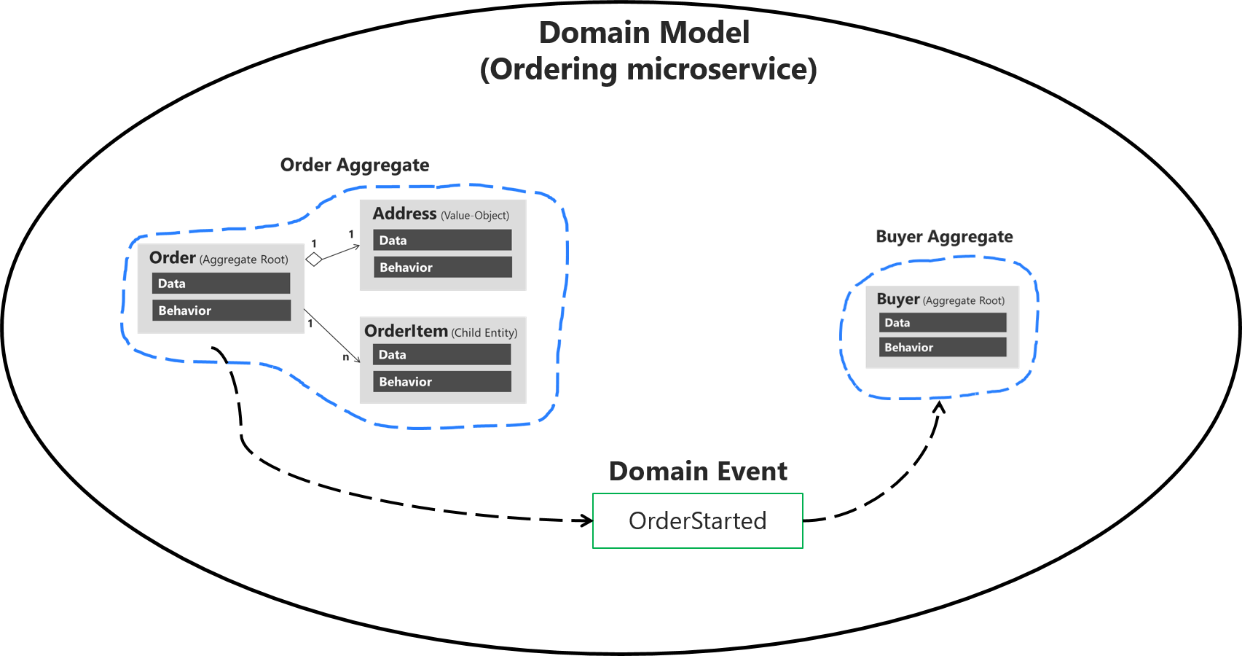

Each business microservice/Bounded Context should have its own “domain model” that captures the business rules, behavior, language, and constraints for that particular microservice/BC.

Domain Entities represent domain objects. They typically have an identity associated with them, and often provide several methods (alongside their data) to implement different behavior.

Value Objects describe characteristics of an entity. They are not necessarily entities themselves because they do not have an identity; they are mainly used to represent state or to hold context.

Aggregates describe a cluster/group of entities that should be treated as a cohesive unit. For example, you may want to aggregate a list of items alongside your order.

Aggregates typically have at least one “root” or “primary” entity. The aggregate root maintains the consistency of the aggregate and acts as the entry point for updates or operations. All operations on the aggregate should go through the root.

The Domain Model Layer

The eShopOnContainers application groups its domain entities and related classes according to their aggregate. This is by no means the only way to structure your application.

The domain model layer defines any interfaces needed to communicate with the infrastructure. The actual implementations for these are defined elsewhere, in the infrastructure layer. This allows the domain model to not be “contaminated” by infrastructure-specific code.

The eShopOnContainers uses a “SeedWork” directory to hold custom base classes that provide common behavior.

You might have an Entity base class that holds common code, as well as things like the IAggregateRoot “marker interface”.

Other valid names might be “Common” or “SharedKernel”.

Your domain entities are ideally going to be normal POCO classes, as well as any operations that will be applied against them. When working with aggregate roots, it is also your job to guarantee that all operations follow your business rules.

All application-layer code must rely on these provided operations.

Remember that all interactions with the business entities should happen through the aggregate root. The application layer’s job is to simply interface with the aggregate root.

In order to prevent misuse, you should never have public setters on your aggregate properties. You should have specialized setters for each valid operation that can be performed. All setters should be private or at least readonly.

Value objects also have their own special implementation requirements (mainly that they lack identity information).

Domain entities should always be in a valid state. An entity should not be able to exist without being valid. For example, an object must always have a positive integer quantity.

If you define errors out of existence, you no longer have to write checks or tests like “is Name not null”. You can be guaranteed that a value exists and is valid.

Domain Events (Application Layer)

Domain events are used to propagate information between the domain layer entities, while integration events are used to handle changes between different (micro)services.

Domain events are created and handled completely inside their respective service.

Domain events allow you to decouple your business rules from your business logic. Instead of performing an action, then immediately calling code to validate it, you can just send off an event. By sending out events, you also have the option of attaching multiple handlers to it.

Sometimes certain aggregates require additional business rules to be enforced on other aggregates. You can implement this using a domain event.

Event handling is considered an application layer concern. Do all your handling in the application layer. Your handlers may need access to things like repositories or an application API, so the application layer is the most appropriate for them anyway.

The Command pattern is typically used to implement domain events.

The basic approach for raising and handling events looks like this:

-

Send a command (eg.

CreateOrder). -

Receive the command in a command handler.

-

Execute a transaction on an aggregate.

-

(Optional) Raise further domain events for side effects (eg.

OrderStartedDomainEvent).

-

-

Handle domain events using any number of side effects. For example, processing an order might require:

-

Verifying the buyer and payment method.

-

Creating and sending an integration event to the event bus to notify other microservices.

-

…

-

Similar to integration events, your domain events will typically be data-holding objects:

public class OrderStartedDomainEvent : INotification

{

public string UserId { get; }

public string UserName { get; }

public int CardTypeId { get; }

public string CardNumber { get; }

public string CardSecurityNumber { get; }

public string CardHolderName { get; }

public DateTime CardExpiration { get; }

public Order Order { get; }

public OrderStartedDomainEvent(Order order, string userId, string userName,

int cardTypeId, string cardNumber,

string cardSecurityNumber, string cardHolderName,

DateTime cardExpiration)

{

Order = order;

UserId = userId;

UserName = userName;

CardTypeId = cardTypeId;

CardNumber = cardNumber;

CardSecurityNumber = cardSecurityNumber;

CardHolderName = cardHolderName;

CardExpiration = cardExpiration;

}

}

Domain events are typically published using things like an in-memory mediator, IoC container, or other methods, unlike integration events which are published using strategies like service buses, queues, databases, or mailboxes. The MediatR library is a popular method for dispatching events.

Your application handlers may talk to different aggregates in order to implement side effects, save data to different repositories, or even publish new integration events.

Infrastructure (Persistence) Layer

The infrastructure layer contains any code necessary to interface with your databases and other services. This is where you will find implementations for the repositories defined in the domain layer.

Repository implementations are classes that encapsulate the logic required to access data sources.

A repository should represent one aggregate or aggregate root. This does not mean you need a repository for each of your database tables.

Repositories should be the only method by which you update the database. It is OK to query the database through other means (ie. a CQRS approach), but updates should always be controlled by the repositories and aggregates.

Repositories aren’t always needed though. You can get away writing infrastructure code inside your commands.

Commands and Command Handlers

Events may be processed multiple times because multiple services may be interested in that event.

Ideally, you should make your commands idempotent whenever possible or practical so that if it does happen to be handled multiple times, you have some protection against it.

Commands are sent directly to their (single) receiver; they are not published like events.

Commands are typically represented as a normal class with data fields containing the information needed to execute the command. Commands are a special type of Data Transfer Object (DTO) used to request changes or transactions.

[DataContract]

public class UpdateOrderStatusCommand

:IRequest<bool>

{

[DataMember]

public string Status { get; private set; }

[DataMember]

public string OrderId { get; private set; }

[DataMember]

public string BuyerIdentityGuid { get; private set; }

}

Command handlers live in the application layer since they may need access to any infrastructure or repositories. The business logic is still implemented in the domain layer; the purpose of the command is just to call the right methods.

Command handlers that are too complex can be a code smell. Consider moving any domain logic into the domain layer rather than keeping them in the command handler.

The result should be either successful execution of the command, or an exception. In the case of an exception, the system state should be unchanged.

Command handlers typically follow the same process:

-

Receive the command object or DTO (from a mediator or other infrastructure object).

-

Validate that the command is valid (if not already validated by the mediator).

-

Creates an instance of the aggregate root instance targeted by the command.

-

Executes the requested action on the aggregate root.

-

Persists the new state of the aggregate to the database. This is where the transaction takes place.

It is not recommended to call your command handlers directly from inside your ASP.NET Core controllers as this would cause too tight coupling. Use a mediator instead.

The MediatR library is a small and simple open-source library used to provide features of the mediator pattern.

Here is an example controller that makes use of a mediator:

public class MyMicroserviceController : Controller

{

public MyMicroserviceController(IMediator mediator,

IMyMicroserviceQueries microserviceQueries)

{

// ...

}

}

Executing a command through the mediator is also quite simple:

[Route("new")]

[HttpPost]

public async Task<IActionResult> ExecuteBusinessOperation([FromBody]RunOpCommand

runOperationCommand)

{

var commandResult = await _mediator.SendAsync(runOperationCommand);

return commandResult ? (IActionResult)Ok() : (IActionResult)BadRequest();

}

You can also attach any cross-cutting concerns or “behaviors” to your mediators like logging and validation that get executed before the command gets sent out.

Reflection/Future Work

Honestly, this book was very long and very boring, but somehow I managed to stick it through to the end, and I felt that I got a lot out of it. That being said, I definitely spent way too long on this project than I really should have. Reading through the book (~300 pages), taking notes, and writing this post took ~29 hours over the course of 4(!) months. Part of this was me being lazy over the holidays, another part was me putting this project on hold while I was preparing for job interviews, and a final part was me procrastinating on reading. I really do need a better system for managing larger reading projects like this one. At some point during those 29 hours, I felt that I learned everything I was going to learn from the book, and I should have stopped right then and there. Being able to finish what I start is normally a great skill to have, just not in this case.

I didn’t yet get a chance to explore the eShopOnContainers codebase, but it’s definitely something I’m inclined to do later on. I happen to finally have some coding ideas that seem promising, and I’d like to start working on those now that this project is out of the way.